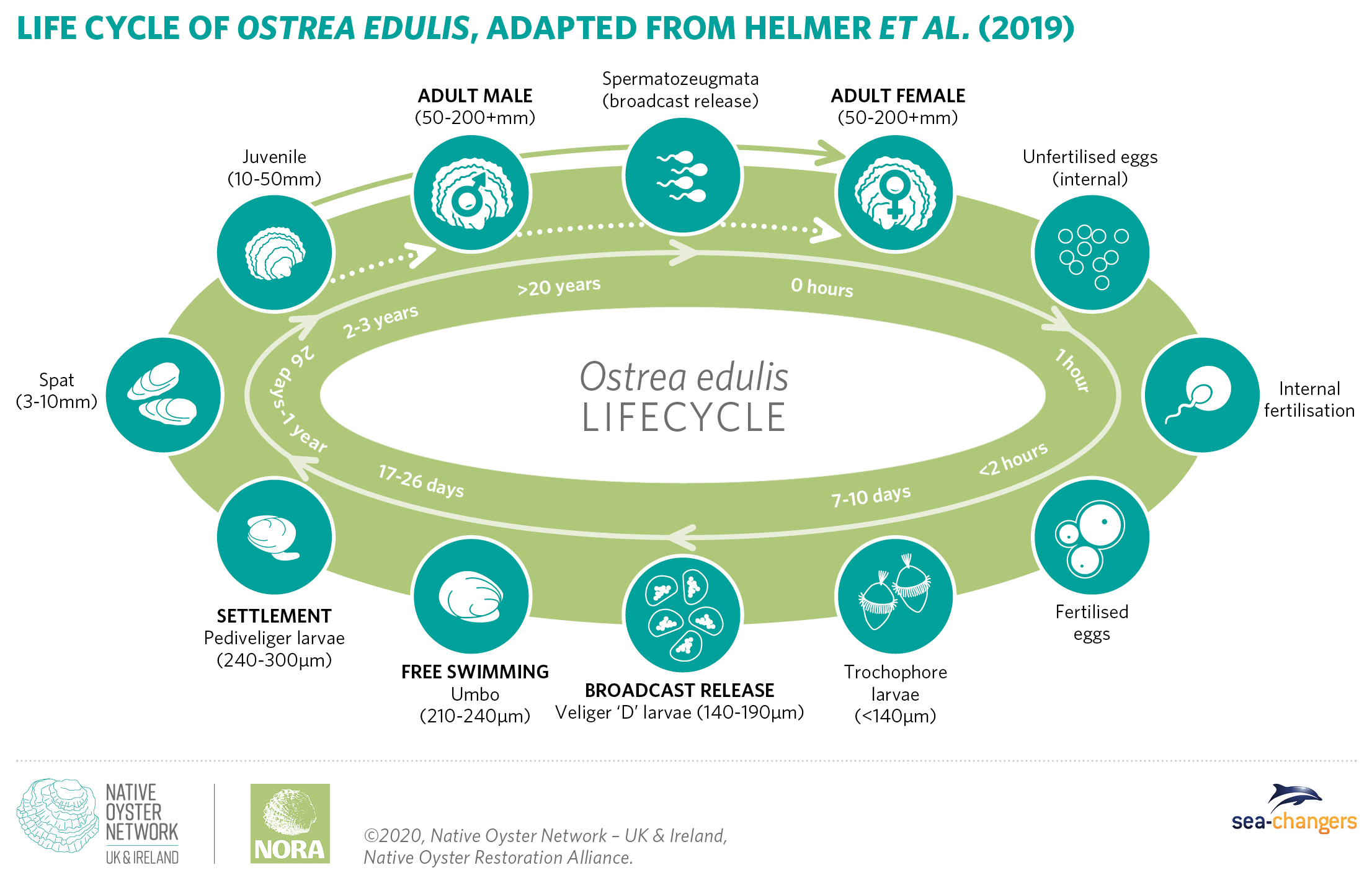

Overview of the species Ostrea edulis

Biology

The European native oyster (Ostrea edulis) is a bivalve mollusc that is typically associated with shallow, subtidal coastal and estuarine habitats. The native oyster has a rounded, rough shell with a pale green, yellow or brown colouring, and when mature are around 5-20 cm in length.

Oysters are filter feeders, they use their valves to pump water across hair like gill structures to filter out microscopic algae and small organic particles from the surrounding water, which serve as the oyster’s food. Native oysters have a fascinating life history trait, whereby an animal can alternate between male and female several times throughout its life, defining them as a protandrous hermaphrodite. The native oyster is characterised by slow growth rate and sporadic recruitment success, the number of oysters surviving to maturity can vary hugely from year to year, making it a particularly vulnerable species.

Oyster reefs

Left undisturbed, oysters will form complex reef structures, which provides habitat and refuge for a diversity of organisms, such as juvenile fish, crabs, sea snails and sponges. Native oyster reefs and beds (hereafter reefs) are formed when large numbers of living oysters and dead shells form an extensive biogenic habitat on the sea floor. Oyster reefs typically form on mixed substrate, in shallow waters less than 10 meters deep, although they have been found to depths of up to 80 meters.

Population

Native oyster populations have declined by 95% in the UK since the mid 19th century and are now predominantly found in the south east; the Thames Estuary, the Solent and the River Fal. This decline makes native oyster reefs one of the most threatened marine habitats in Europe. Across Europe the native oyster is found from the Norwegian Sea to the Atlantic coast of Morocco, and in the Mediterranean basin. Populations in Europe faced collapse in the mid-20th century due to overfishing, pollution, disease and the introduction of invasive species. Oyster reefs are globally imperilled, with an estimated 85% loss worldwide.

CONSERVATION STATUS

UK Biodiversity Action Plan Priority Species and habitat, UK-post 2010 Biodiversity Framework with its own Species Action Plan.

Species of principal importance for the purpose of conservation of biodiversity, Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006.

OSPAR List of Threatened and/or Declining Species and Habitats (Region II – Greater North Sea and Region III – Celtic Sea).

Native oysters and native oyster beds are a “Species and Feature of Conservation Importance respectively (SOCI and FOCI) under Marine and Coastal Access Act.

Nationally scarce habitat.

- BBC Wildlife Magazine: https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/marine-animals/8-facts-about-flat-oysters/

- JNCC: https://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-5659

- MarLIN: https://www.marlin.ac.uk/species/detail/1146

- FAO: https://www.fao.org/fishery/culturedspecies/Ostrea_edulis/en

- WoRMS: https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=140658

WHY OYSTERS ARE IMPORTANT?

Native Oysters provide us with a range of ecosystem services and hold both economic and environmental importance.

WATER QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

Oysters filter algae and organic matter from the water column, which can significantly improve surrounding water quality by decreasing the turbidity (a measure of the amount of suspended material in the liquid).

INCREASED BIODIVERSITY OF SPECIES

The unique 3-dimensional habitats created by native oysters support a higher biodiversity of species than the surrounding sediment/seabed. By providing a structure colonised by algae tunicates, sponges, crabs, crustaceans and ascidians

NURSERY HABITAT FOR FISH

Oyster reefs can increase fish abundance and biodiversity by providing a protected nursery ground for juvenile fish, refuge from predation and a source of food resulting from the associated biodiversity.

REDUCE NITROGEN LEVELS

Oysters have the ability to remove excess nutrients from water, particularly nitrogen, which at high levels can be detrimental to the environment by promoting harmful algal blooms, depleting oxygen and fish death.

CULTURAL VALUE

Native oyster fishing and cultivation have formed the heart of coastal communities in the UK and can be traced back to Roman-times.

THREATS

Historic overfishing

Habitat loss

Disease

Bonamiosis – caused by the haplosporidian Bonamia ostreaea Marteilia refringens

Oyster herpesvirus (OsHV1)

Pollution

Tributyltin (TBT)

Invasive, non- native species

American slipper limpet Crepidula fornicata American oyster drill Urosalpinx cinerea

Predators

Oyster drill Ocenebra erinacea Common shore crab Common whelk Buccinum Undatum

How to tell the difference between a native oyster and a pacific oyster?

Native oysters are characterised by a rounded, flaky shell with a brownish green colouration. Whereas pacific oysters have an elongated shell with sharp curved edges, typified by a purply pink colouration. Pacific oysters are normally established in the intertidal zone in coastal areas and muddy estuaries so can be spotted whilst walking along the shoreline at low tide. However native oysters are located in the lower intertidal and predominantly sub-tidal zone, so you’d be more likely to find them whilst on a dive.

Ostrea edulis

Native oysters

Native oysters have formed an important part of our cultural heritage and native oyster fisheries have sustained livelihoods for UK coastal communities for hundreds of years. Further to this, Native oyster reefs provide a nursery area for a diversity of fish species, including commercially important species such as sea bass. Known as ‘ecosystem engineers’ because they create the conditions for other species to thrive – stabilising shorelines, filtering water and providing vital food and habitat for coastal wildlife. One adult oyster, for example, can filter more than 140 litres of water in a single day. They’re also able to bury carbon into the seabed as well as remove nitrogen from the water, recycling it into their shell. Collectively the oyster beds in the Solent have the potential to remove 200,000kg of Nitrogen each year, which is roughly the weight of 33 African Elephants.

Crassostrea gigas

Pacific oysters

In 1965, the Pacific oyster was introduced to the UK to replenish the low stocks of the UK native oyster. It is native to the Pacific Coast of Asia. It was previously thought that our UK seas were too cold for Pacific oysters to successfully reproduce, however they have now become established in the wild in many places along the UK coastline such as Cornwall and Devon.

Many thanks to Jake Davies, Stephane Pouvreau, Luke Helmer, David Smyth, Alice Lown and the Solent Oyster Restoration Project for providing images used on this page!